The Rebellious Women of Coigach

Remembering women from days gone by ~ IWD - Daisy Chain Flower Crown

This is a long post which means it will appear as clipped or truncated in an email. To see the whole thing just press VIEW ENTIRE MESSAGE at the end of the email and you’ll see it in one. Or head to the online version. Grab yourself a cuppa and read on…

Last week,

and issued an invitation to join in a creative act of friendship, solidarity, reciprocity and connection in celebration of International Women’s Day. To create a virtual ‘daisy chain’; daisy chains being something girls and women have sat together and made for time immemorial.To remember days gone by and take a breath to integrate how far we’ve come since we made the first chain. To make a virtual flower crown for each other and wear it with pride.

In the spirit of International Women’s Day, I am sharing a piece that I wrote last year for History Scotland magazine. It celebrates the role the women of a small crofting community played in rebelling against their landlord’s attempts to evict them from their homes. It’s important that we remember the women who have gone before us, most of them nameless, who have stood up for what was important to them and built the foundations for later generations.

Previously, I shared the story of the role Croick Church played in one episode of clearance within the Highlands in the 1800s.

This piece relates another episode in that time of social upheaval, almost 10 years later.

Throughout history women have generally been silent. However, during the time of clearance in the Highlands, the women were far from silent, often playing a leading role in the resistance to eviction.

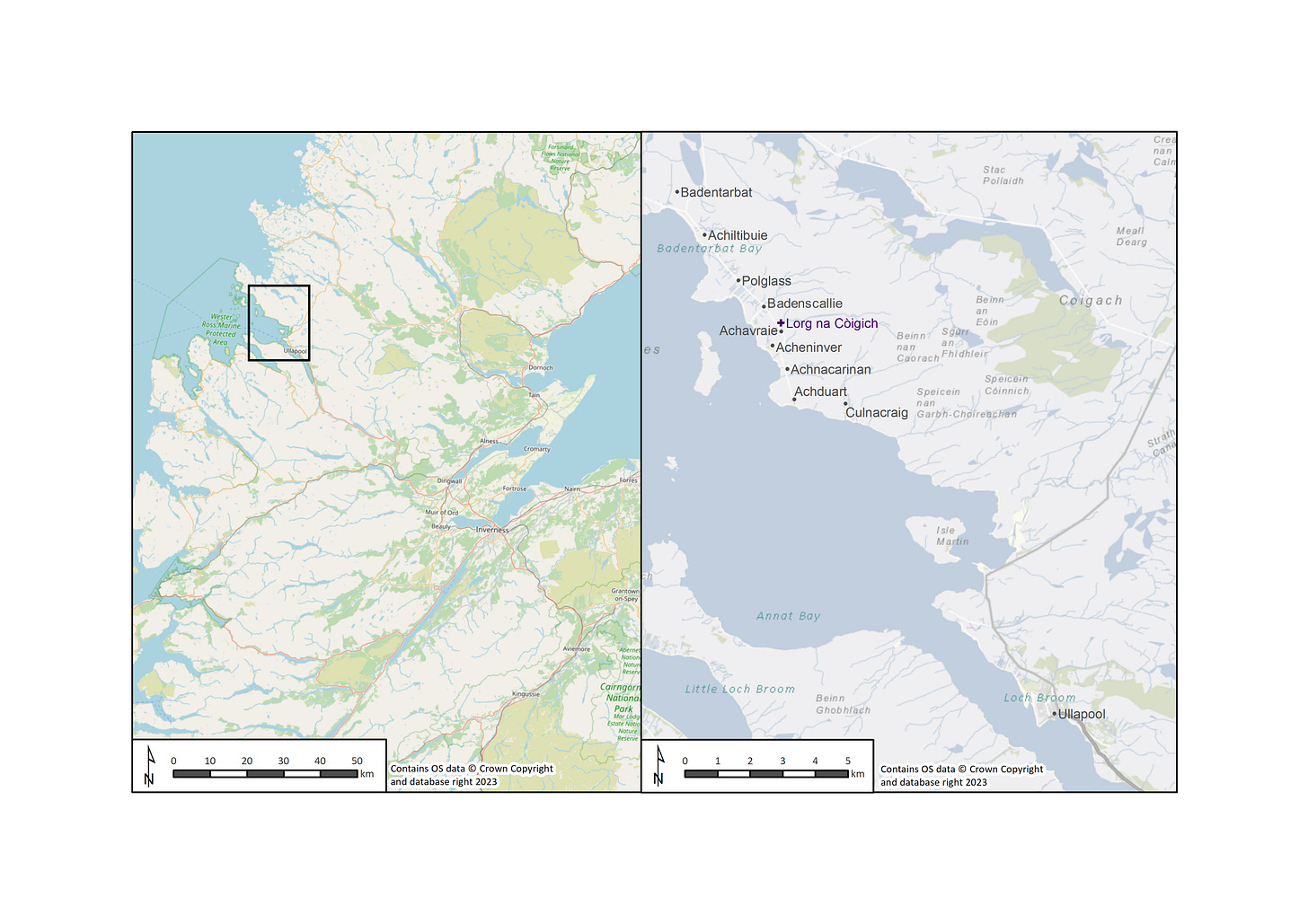

Coigach, a peninsula in Wester Ross, Scotland comprising several small townships, found itself under the national gaze during 1852 and 1853 when five attempts were made to remove sub-tenants from their land within the townships. Through sustained resistance, these attempts were wholly unsuccessful. At the forefront of this resistance stood the formidable women of Coigach who were described by the Inverness Courier as a

‘band of Amazons’ displaying ‘everything but hospitable intentions in the reception of the unwelcome’ sheriff’s officer.

Each time he landed, the ‘brawny beauties’ seized the writs and burnt them. Completely defying Victorian narratives of femininity, the women of Coigach fought passionately and ferociously for their homes.

The Barony of Coigach in Wester Ross had been the westernmost extremity of the Mackenzie’s Cromartie Estate since 1609. In the early 1800s, the Coigach peninsula was heavily populated and poor. The then laird, John Hay-Mackenzie, was benevolent but debt-ridden. In 1849, financial ruin loomed; ruin that was averted by the marriage of his daughter, Anne, to the Marquis of Stafford, followed two weeks later by her father’s death. In the years following the Coigach land struggles of the 1850s, the Marquis, heir to the Duke of Sutherland, would become one of the wealthiest men in the country, but, until then, the Cromartie Estate could not count on the Sutherland fortune to subsidise it.

In 1852, with the estate under financial pressure, Andrew Scott, the estate factor, decided that it was time to ‘rationalise’ the land use at Coigach. Specifically, there was a large farm at Achiltibuie and Badenscallie that was densely packed with sub-tenants. The tacksmen, or main tenants, of this farm were complaining so vociferously about their sub-tenants that Lady Stafford agreed to terminate their lease. Prospective new tenants would only take on the lease without the sub-tenants.

Scott was able to persuade the majority of the sub-tenants to sign an agreement to relinquish their hillgrazings and resettle at Badentarbat. However, eighteen families refused to sign; not only would they lose their hillgrazing but also their landholding. Scott angrily stated that they had

‘stirred up all the other people in their townships to resist the removing in any way or under any modification whatever’.

It was a typical standoff: the landlord wanted to make a more profitable return on a portion of land but the sub-tenantry was in possession and, understandably, didn’t want to leave their homes.

Service of summonses of removal on the recalcitrant eighteen was the next step. Scott, knowing that this would probably be met with physical resistance, requested police accompaniment for the serving party. On 18 March 1852, they went from Ullapool to Coigach where they were met by a large crowd of people, principally women, who seized and searched each of them for the writs, which were burnt once discovered to prevent service being effected. Defeated, and undoubtedly humiliated, the sheriff’s party was forced to withdraw.

A week later, another attempt was made to serve the notices. A larger party again made their way by boat from Ullapool. There must have been a sense of trepidation as they sailed along the coast on seeing several hundred people amassed. They went firstly to Achnahaird and then to Achiltibuie. At both places, they were unable to serve the summonses, being outnumbered by the ‘mutinous’ crowds. At Achiltibuie, a large crowd gathered on the beach below the hotel where the boat landed. A number of women and teenage girls seized the Sheriff's men and stripped them, looking for the summonses. Failing to find them on their bodies, they searched their boat and found them nailed under the sole at the stern. The papers were taken and burnt in a bonfire on the beach. The boat was then carried up the hill, dumped on top of a potato pit just below the hotel and left there. Scott described the events of the day as

‘a distinguished triumph of brute force over law and order’.

Scott was determined that the crofters should be cleared and was supported in these plans by the Marchioness who told him

‘I think the sooner and the more decidedly the Badenscallie people are taught their lesson the better’.

With a further attempt at serving the writs impending, scouts were positioned at Ullapool to give warning of a party leaving there. The anticipated confrontation occurred in the second week of February 1853. The sheriff’s party landed at Culnacraig whereupon the sheriff’s officer was seized by the women; the writs were once again taken from him and burned. The officer was then

‘entirely stripped of his clothes and put on board the boat, in which he went to Coigach, in a state of almost absolute nudity’.

Scott by this time felt that

‘no force other than a military force [would] be sufficient to bring the people to submit’.

A request to the Solicitor General in Edinburgh for a party of soldiers or police from Glasgow to support the local officers was refused. Instead, another attempt had to be made by the ordinary law officers reinforced by a police presence. Consequently, on 22 March 1853, it was, yet again, the Sheriff Depute, Procurator Fiscal, and some of the County Police who set off from Ullapool by boat. On landing at Culnacraig, the party

‘were met by a great body of people consisting of two or three hundred persons (chiefly women, the men being in the background)’.

The crowd paid little heed to the Sheriff’s address to them as, once he had finished,

‘they rushed upon him and the four policemen by whom he was surrounded and seizing him and then violently deprived him of the writs, which…they immediately destroyed’.

Katie Campbell, one of a handful of named women present, took the shoes of the leader to ensure that no papers were secreted there and the officer was subsequently thrown in the sea. Yet again the law had been defied and its officers humiliated at the hands of the crofters (1); humiliation that was compounded by extensive newspaper coverage throughout the resistance, locally and nationally.

As late as December 1853, action against the Coigach crofters was still being demanded. However, the adverse publicity and general unpleasantness surrounding the issue finally persuaded the Marquis and Marchioness to abandon the proposed removals. For the people of Coigach, it was an almost unprecedented victory in Highland history; rarely, if at all, had the authority of a clearing landlord been successfully resisted. A success largely won by the women.

Unlike the male players on both sides of the proposed removals, the women are nameless within the written records. Oral history, however, has ensured that five of the female leaders are known: Mary Macleod, Anna Bhan Mackenzie, Katie Macleod Campbell, Margaret Macleod (aged about 16 at the time of the rebellions)(2) and Catherine Stewart. Katie was later identified by estate officials and officers demanded that the factor make certain that she could never live on the Estate. As a result, when she married, she and her husband were forced to build a house below the high water mark on the shore, which was frequently flooded.

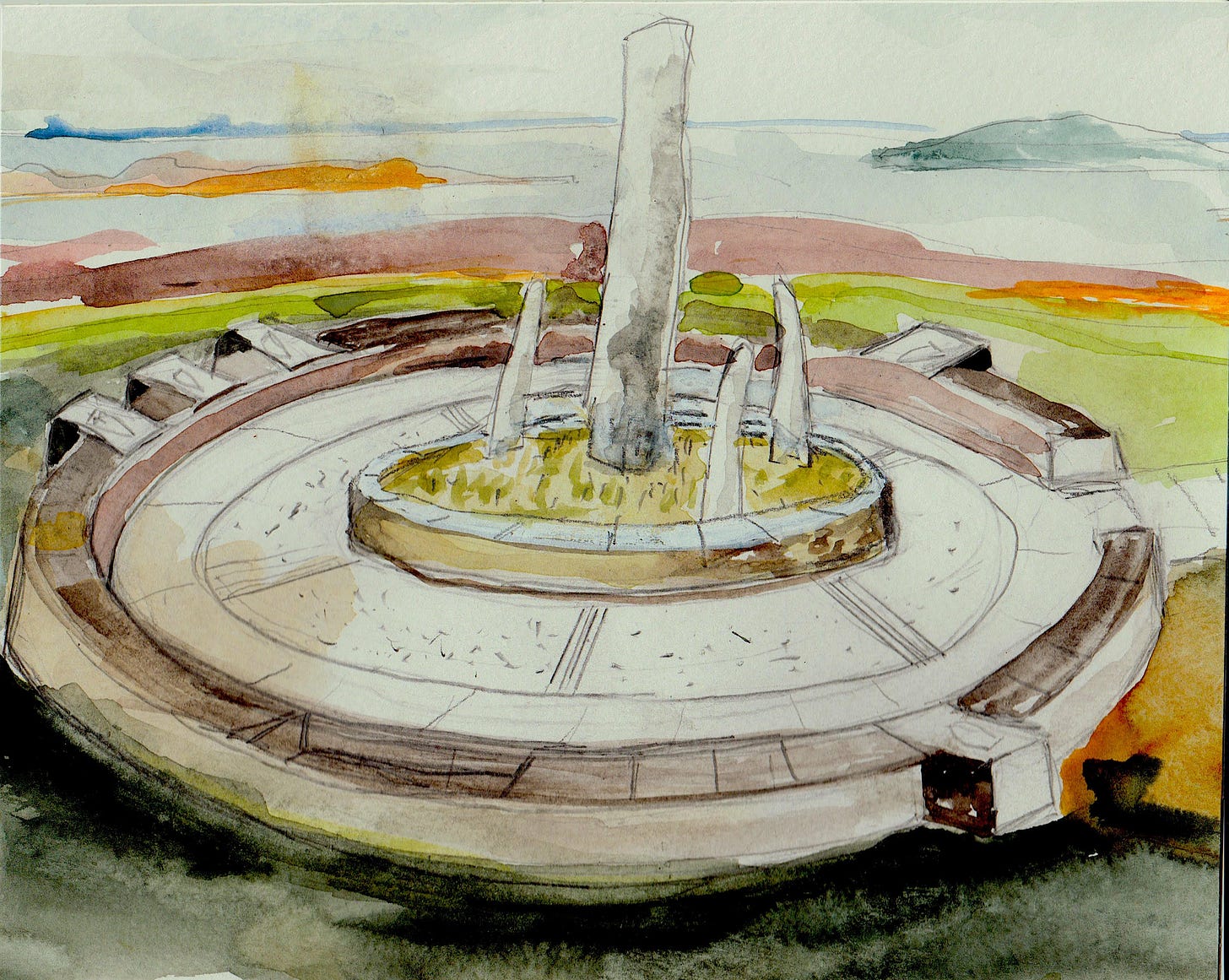

To recognise the efforts made by these women within their community, efforts that have ensured the continuity of some of those families within today’s community, Coigach Heritage has launched a fundraising campaign for an exciting new community project. Internationally acclaimed local artists, Will Maclean RSA and Marian Leven RSA, have designed a landmark monument, Lorg na Còigich (the footprint of Coigach), to be set on the hillside above Acheninver, near Achiltibuie. Every stone will symbolise the women, and men, who made a stand against injustice. The memorial will be a visible celebration of a female story that has been silent too long.

Many thanks for sharing this, really found it fascinating!

Thank you for sharing this wonderful story of bravery and determination.

I have visited Coigach many times - it is one of my favourite locations on the west coast but I had never heard this story. The memorial seems a fitting way to remember these brave women and I hope to see it one day.